I was perusing my Google reader and to my delight came across an article in PNAS by Lindenmayer et al. (2010) called, "Improved probability of detection of ecological surprises." In it the authors describe four long-term research programs that have led to both ecological surprises as well as ecological discoveries. From these important surprises and discoveries, the authors derive four "lessons." They further argue that we should provide more financial support to long-term experiments, encourage scientists to develop natural history skills, increase collaborations among different disciplines, and provide an environment where time is plentiful.

After reading the article, I thought to myself, "Haven't I been saying that ad nauseaum in my Slow Science Series?" Hmm, maybe I should stop with the blogposts and focus on the manuscripts, after all my CV sure could use a few more lines.

Nah. As HippieHusband points out I probably have more people reading my blogposts than people reading my science pubs. Plus you can't add cheeky personal commentary in manuscripts.

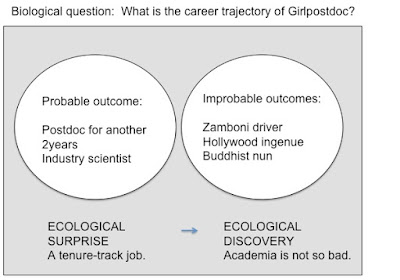

Let's start with how the authors define ecological surprise vs. discovery. A surprise is most obviously defined as an unexpected finding about the natural environment. But it occurs outside of what is considered expected and probable and that which is improbable.

A discovery, on the other hand is simply something that provides new insight or understanding that may help to elucidate something already hypothesized. Discoveries often start with surprises but come from a series of meticulously designed experiments. This definition leads to the implicit assumption that chance plays a larger role in ecological surprise than it does in discovery. And that surprises can lead to new discoveries.

Lindenmayer et al. (2010) present four long-term studies where ecological surprise changed both the story of what was happening in the ecosystem and the direction of a research program. The four were the Hubbard Brook Ecosystem (Northeastern USA), Kluane Boreal Forest Ecosystem (Yukon Canada), Wet Forest Biodiversity Study (Victoria, Australia), and the Serpentine Grassland Dynamics(Northern California). Two things struck me about these case studies. First, the ecosystem was not just studied by one type of scientist. These were multi-faceted research programs involving scientists from a variety of disciplines. Different research projects in the same ecosystem acted like multiple strands of thread that when woven together told a surprising and important story. But importantly, this last part came as a function of time. Each of these studies has been running for more than 25 years.

Rather than go into detail about each of the cases, I want to focus on what lessons the authors argue we can learn from these cases. First, they believe that ecological research should have as its basis a strong conceptual model or a good question. Second, using the literature (deep past) is important to developing strong hypotheses and alternative views of ecological systems. Thirdly, well-designed experiments are at the heart of good science and can lead to robust outcomes.

Lindenmayer et al. (2010) aren't really saying anything new. One missing aspect is something that Stephen Jay Gould said in the Lying Stones of Marrakech.

"Objectivity cannot be equated with mental blankness; rather, objectivity resides in recognizing your preferences and then subjecting them to especially harsh scrutiny - and also in a willingness to revise or abandon your theories when the tests fail."

Meaning two things. When you set out to test your favourite hypothesis (because inevitably as researchers we have a pet theory), recognize those prejudices and be your own harshest critic.

For me, one of the most salient lessons was the connection between ecological surprise and the interaction between long-term studies and a range of different kinds of research on a single system. Long-term studies are useful because they can identify the relationships between different ecological patterns and the connections between ecological processes. But only because different types of researchers collaboratively work for a long period of time on different aspects of an ecosystem.

In a world of personal genomes and next-generation sequencing frenzy, Lindenmayer et al. (2010) believe that the chance of witnessing an ecological surprises will be increased if more individuals conduct field-based empirical work and possess natural history skills (The Sniper Scientist). These are skills that as an evolutionary geneticist, I am wholly aware, I do not have. I am also cognizant that this special species of researchers is going extinct.

But after all this, is it enough? Not according to the authors. The last ingredient is time.

"Researchers at the Hubbard Brook Experimental Forest, as well as those in the three other case studies, further increased their chances of detecting eccological surprises because they had time to think long and deep about the phenomenon they were observing in the field. This is the antithesis of much of modern scientific culture, which we argue is often affected by an "epidemic of busyness" created by cell phones, e-mail, and other rapid communication technology as well as the comparative ease of travel to meetings worldwide."

After all the theory of natural selection was not built in a day.

2 comments:

Lovely! Very well written and so interesting. Thanks for explaining some of this ecological stuff to a non-eco person (non-eco in the professional way, not the standard "I like ecology").

:)

I've enjoyed the whole slow science series and it has a lot of thoughts in there... just need to get back into pondering mode again (me after holidays, that is)

There probably isn't "one" way to do science; different approaches are probably needed for different research.

Anyway, this discovery might fit within your paradigm:

http://www.usatoday.com/communities/sciencefair/post/2010/10/2010-physis-nobel-prize-reaction-round-up/1

Post a Comment